What is Sundown and how did it come to be?

My work represents a profound act of love and witness, transforming my devastating experience of watching Alzheimer’s disease claim my father into something that honors both his memory and the universal struggle families face with this disease.

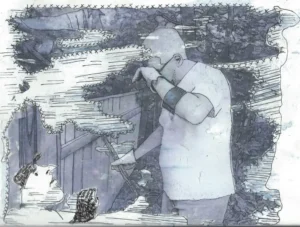

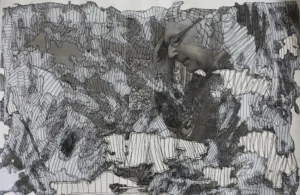

The technical choices I’ve made are significant—the gel medium transfers create that crucial layer of removal from reality that mirrors how memory itself becomes increasingly distant and fragile. The deliberate degradation of images becomes a visual metaphor for the disease’s progression. At the same time, my ink additions serve as a bridge between what was lost and what remains, between documented reality and the interior landscape of illness.

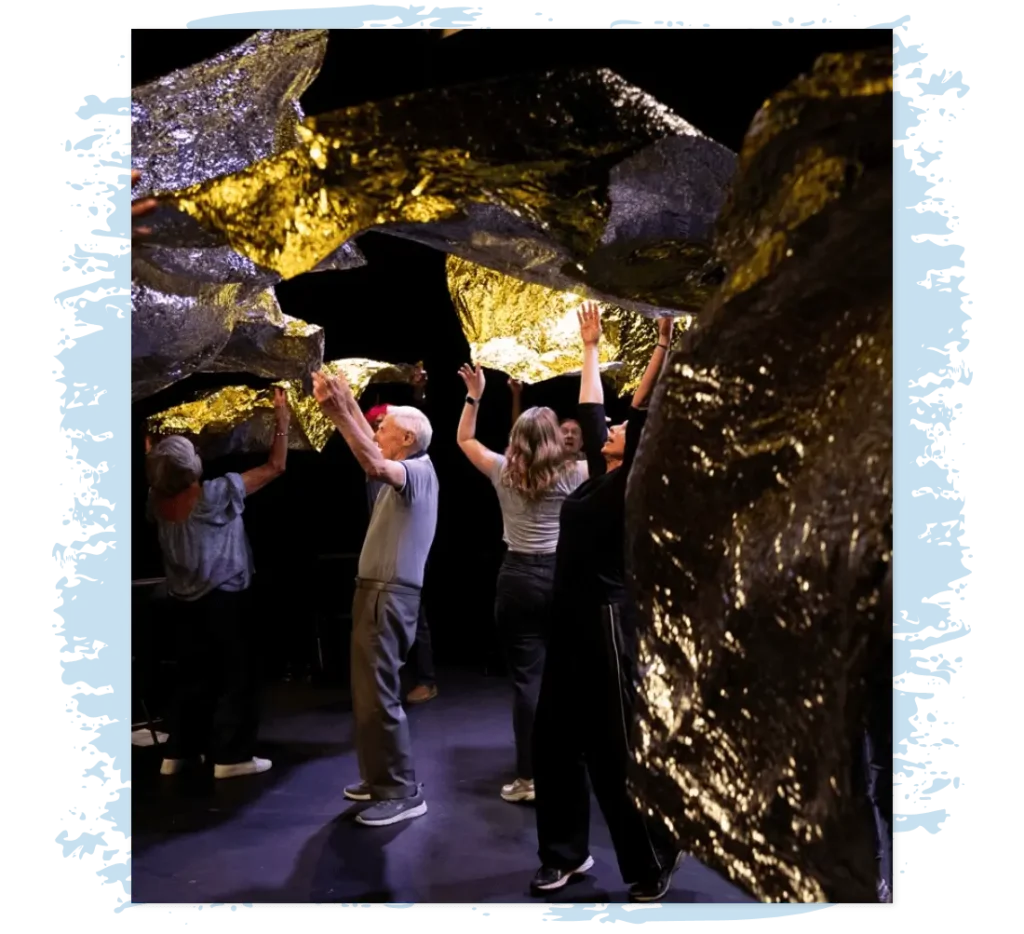

What strikes me most is how I’ve found ways to externalize the internal experience—both my father’s sundown hallucinations and my emotional journey through grief and loss. The mixed media approach allows me to capture what straight photography cannot: The emotional texture of watching someone disappear while still physically present, the anxiety and confusion that pervade daily life, and those alternate realities that sometimes provide comfort.

My work serves multiple audiences. For those who haven’t experienced Alzheimer’s disease, it offers essential insight into the slow-motion devastation. For families currently navigating this journey, it provides recognition and perhaps solace in shared experience. And ultimately, it stands as a testament to my father’s life and my enduring love for him.

By creating beauty from such profound loss, I’ve transformed personal devastation into something that can speak to others facing similar darkness, offering both witness and understanding.

Who initially inspired you to grapple with dementia?

The initial inspiration to grapple with dementia came from the profound need to make sense of an incomprehensible loss. When my father was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s at 64, I was confronted with watching the most important person in my life slowly disappear while still being physically present.

The traditional tools of grieving felt inadequate for this particular kind of loss—how do you mourn someone who is still there but fundamentally changed? Photography and mixed media became my way of processing what felt unprocessable, of giving form to the formless experience of watching a brilliant mind fade.

I was driven by the urgent need to preserve something—not just memories of who my father was, but also to document the reality of what we were living through together. The work became both an act of witness and a form of communication, allowing me to express the complex emotions and surreal experiences.

How has working on dementia-related art changed you?

Working on dementia has fundamentally shifted my understanding of what documentary photography can accomplish, but it has also taught me about the power of making private pain public. Having always leaned toward documenting significant moments in my family and surroundings, this project pushed me beyond my traditional photo-based practice when I realized that photographs alone couldn’t capture the nuance of my father’s decline.

The subject made me acutely aware of the fragility of memory and identity, changing how I view aging from something distant to something immediate and precious. However, the raw honesty required—and the mixed-media approach I needed to convey the full emotional complexity—proved too real, too exposed for my family. I learned that some stories, no matter how universal their themes, belong to more than just the artist. This led to careful consideration of who owns the story I’m telling.

How has Sundown been received?

Sundown has been received with profound resonance by gallery attendees, who have expressed gratitude for helping them understand their own journey with dementia or that of a loved one. Many visitors shared that the mixed media approach successfully conveyed the emotional complexity they recognized from their own experiences—something traditional documentary photography had never captured.

However, reception within my own family was starkly different. My father, when experiencing the work, felt slightly uncomfortable confronting the truths it revealed about his condition. The visual representation of his decline forced him to face realities he may have preferred to keep private.

Most challenging was my family’s inability to understand why I felt compelled to make something so deeply private into public art. They questioned whether our shared trauma belonged in an online or in a gallery space, whether my interpretation of our collective experience was mine alone to share.

This work is dedicated to: My father, Michael Brown. 1950-2022

Find more from Ellie Brown on her website and Instagram.