What is 73 Seconds and how did it come to be?

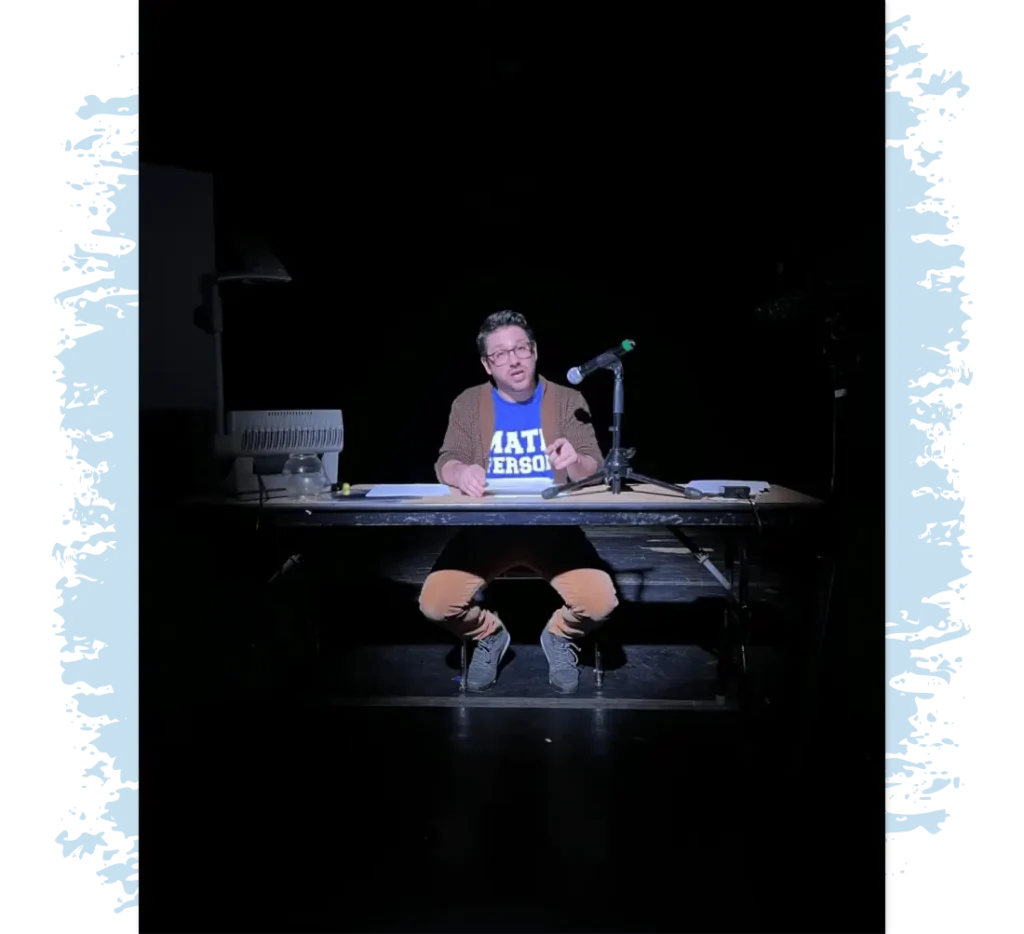

73 Seconds, from En Garde Arts, is a one-man show that tells the true story of a family and what happens when a son finds out his mother, who he knew as a science teacher, was once an employee at NASA and under consideration for a trip to outer space. The multimedia performance takes its events from my own life, where my mother, Rosemary, is living with dementia and I’m attempting to comprehend how to maintain and nurture the stories of our past when only one of us can retain them.

A culmination of my work as a theater director, writer, designer, and performer, 73 Seconds tells the story in three distinct moments of our lives: at NASA, at the death of my father, and in our phone calls throughout the last year. Although my mother struggles to recall the details of the first two moments, she still manages to walk me through grief and suffering. As 73 Seconds tries so hard to grapple with, grief and the embrace of mortality is an ever-growing and ever-evolving process.

Who initially inspired you to grapple with dementia?

My mother, Rosemary, is a person living with dementia. For a few years, this was undiagnosed. During that time, I found myself wanting to understand how my relationship to my mother was shifting as we age. Now diagnosed, I feel more inspired to honor my mother in this piece by recalling some of the most impactful moments of our lives and how our current relationship—while challenging—still demands an intentionality of love, communication, and memory printing that feels particularly meaningful as a piece of theater. Theater has the same temporality of the mind: the moment it happens, it’s gone. And so I’m inspired to create a piece that asks us to embrace the truths of time, mortality, and memory instead of fighting it.

How has working on dementia-related art changed you?

Because it is such a current challenge in my life as I experience this new chapter, I think creating a piece of art has helped me compose my thoughts and actively walk through them. When my father died, I was 19 and was completely wrecked by the experience.

There is a scene in 73 Seconds that depicts the conversation I had with my mother that night. She expressed how she always thought that being a good parent meant finding a way where your child never suffers in life. But actually, suffering is inevitable. We all will face struggles in life, and we eventually have to confront death in very real ways. And so, my mother suggests, maybe it’s not about spending life trying to avoid suffering. Instead, perhaps it’s about embracing suffering as a part of life and, therefore, learning how to be creative with it and how to suffer creatively. While she was talking about the loss of my father, I think her words echo throughout 73 Seconds as an invitation to embrace my mother’s dementia and learn how to cope and exist creatively within it.

Has it changed me? Yes. It’s deepened my love for my mother. NASA be damned, she’s even more of a superhero now.

How has 73 Seconds been received?

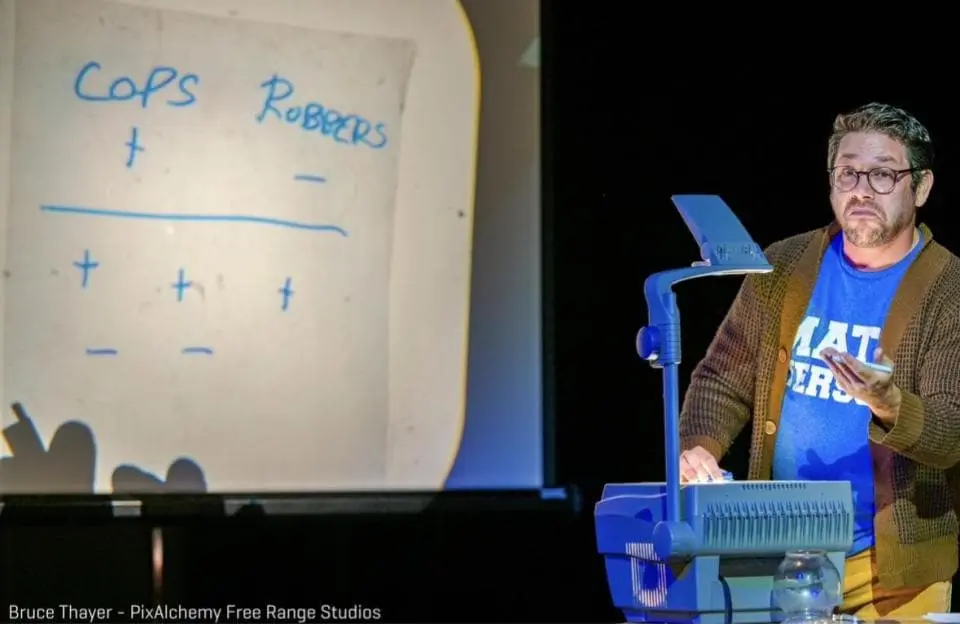

I’ve had the opportunity to perform 73 Seconds twice, both in drafts as a workshop. The first was at The Jefferson Market Library in New York City and then at the Colorado New Play Festival. I perform it with a VHS camcorder, television, and an overhead projector. I mix the use of live camera and prerecorded media between home videos and news from the ‘80s, ‘90s, and today.

I’m proud to see audiences of all ages glean onto different aspects of the piece. Many respond to my relationship with my mother, or the vintage/nostalgic use of media and older technology, but the overall response is around aging parents and—when relatable—dementia. Everyone experiences life with aging parents, and perhaps the dementia side of my mother’s aging allows me to ask the questions in more immediate ways.

The instinct to fight the aging process feels more present in my conversations with audience, which is a primary aspect to my relationship to dementia in family members. We want to retain the former version of our loved ones, which can cause the largest tension. It’s the active pursuit of embracing dementia that makes this chapter particularly graceful and intentional for my mother and I. I’m learning what it means to be creative every day I can be with her, and I think that topic is what moves (and challenges) people the most.

This work is dedicated to: My mother, Rosemary Teresa (Quinn) Mezzocchi, and my family (my siblings, stepfather, aunts and uncles, and step-siblings) who are at the beginning of learning how to navigate this chapter.

Find more from Jared Mezzocchi on his website and on Instagram.