What is The Broken Looking Glass and how did it come to be?

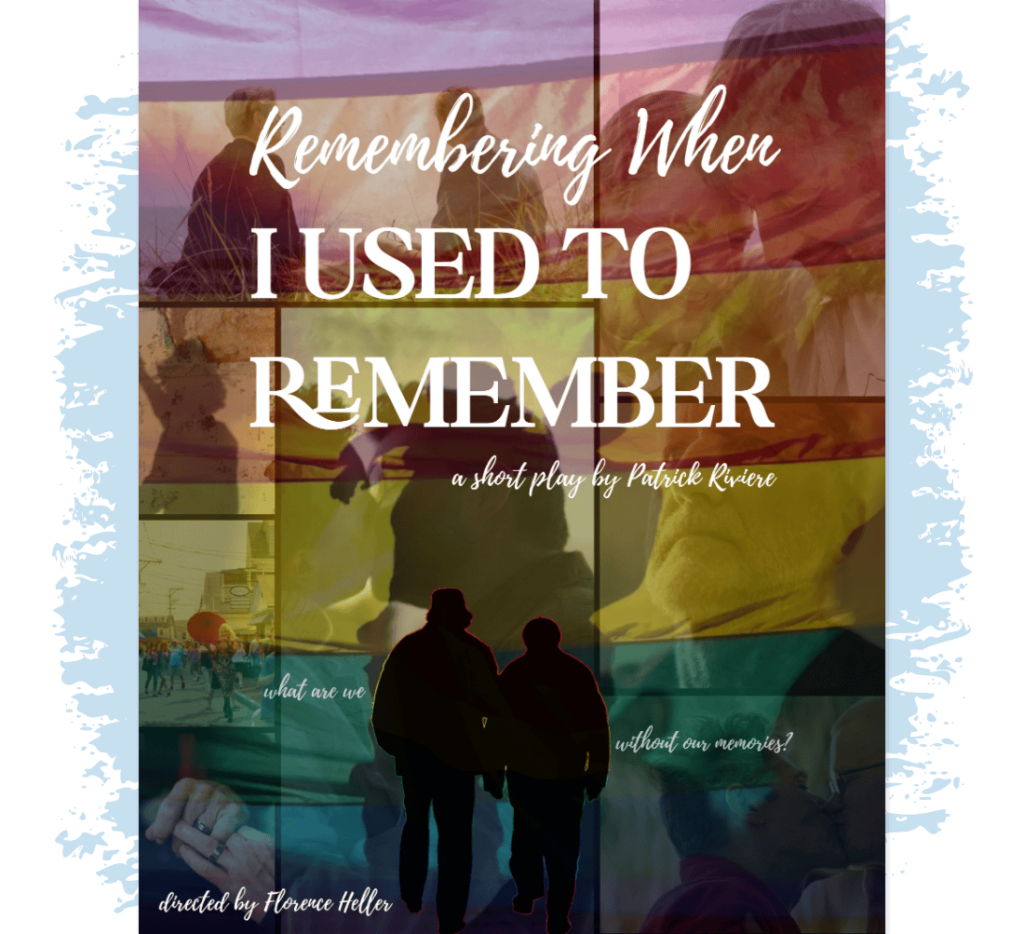

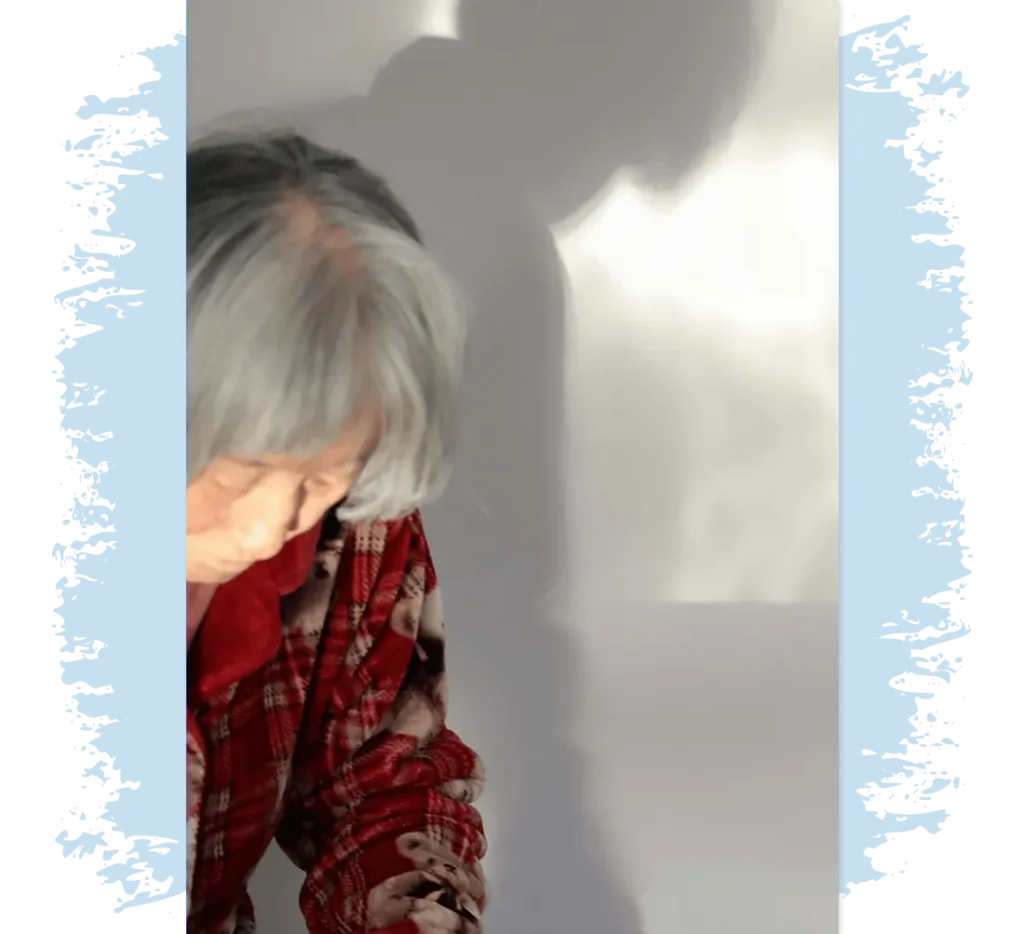

Three years after my mother, Catherine’s, Alzheimer’s diagnosis, and knowing that her real decline had begun, I moved home to be with her and my father, John. I intended to be there for a few months, but I ended up staying for four years, sleeping in my sister’s old bedroom, putting my life on hold. As a means of processing everything that was happening, I took to keeping a written and visual account of my mother’s decline. I turned these writings into a long manuscript and turned that into the feature screenplay I will direct, titled The Broken Looking Glass.

The expanding oeuvre of dementia films has largely ignored the added challenge of caring for a dementia patient with aphasia, which my mother developed quite early. This is a key part of the project and will prove challenging to demonstrate, to say nothing of getting an audience to bear with a feature film where the main character can barely communicate. However, this challenge, this frustration—as demonstrated by the mother’s inability to make herself understood, as well as the other family members’ ability to understand her—is key for the audience to understand. The nature of this project shows the constant 24-hour-a-day challenges, joys, madness, peace, destruction, and love that swirl in a never-ending maelstrom through and around the destruction that Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia create.

Who initially inspired you to grapple with dementia?

Initially, I didn’t want to create anything related to my mother’s struggle with Alzheimer’s. It was too close and too raw. But as time passed, I found myself writing more and more, and, as a filmmaker, that writing lent itself to a screenplay.

It’s important to tell our stories because there are millions of people serving as caregivers for their loved ones who will be seen and heard in the telling. I want people to know that they are not alone. I also want people to know that there are a multitude of ways that the disease can manifest itself and that there are a multitude of ways that people deal with it.

While there are more and more projects, films, videos, shows, and more, there are not nearly enough. For my own part, it has helped me to cope with the entire experience and allows me to share it with others.

How has working on dementia-related art changed you?

In some ways, dementia has increased the immediacy of the work. I’d always wanted to tell stories that matter, but I find myself writing stories and attracted to films that can be more than simply entertainment.

I have always been very interested in dramas, and my strongest work lies in those areas, but very often I have been told that my endings are “too European,” meaning that everything isn’t wrapped up in a nice little bow at the end. This film ends with the acknowledgment that nothing will get better, that this is a permanent, ever-worsening condition, and that the strain it places on family members must be dealt with, and can lead to permanent troubles.

How has The Broken Looking Glass been received?

Everyone who reads the script is supportive of The Broken Looking Glass. My producing partner, who knows my family well, was always supportive, but it has become more immediate for him as well with his own mother’s cognitive decline.

Readers often remark how they can see something in their own loved ones or experience, and think it is important that the film gets a chance to be made and seen.

This work is dedicated to: This piece is dedicated to Catherine, my mother, as well as to my Aunt Eleni, who was, in effect, my second mother, and who died of Alzheimer’s disease. Furthermore, this is dedicated to all of the caregivers, both professional and family, to those who have been, are, and will be caregivers.